Ah mes amis! We have reached the end of our operatic journey together. As I sit here and reflect on where I was at the start of this semester to where I am now, it’s obvious to me how much operatic knowledge and appreciation I have accumulated over the course of the past few months.

When I first walked into Whalen 2330 in January, I was merely a Health Science major in a room full of strangers with no opera knowledge or experience whatsoever. Although I can’t necessarily say that I have fallen in love with the operatic craft, I can absolutely say that I have gained more of an appreciation for the creativity, talent, and beauty that are combined in these performances. I am able to hear an operatic piece and listen to the music rather than the lyrics. I am able to sympathize more with the characters. I am able to feel something more than confusion or indifference when I hear an aria. My perspective on opera has definitely transformed, in that I can now consume opera with a knowledgeable and experienced mindset.

Because I hadn’t had exposure to an opera prior to this class, I was excited — to say the least — to have the opportunity to be an audience member at the Metropolitan Opera House. If I wanted to see an opera, what better way do it than at one of the most prestigious opera houses in the world? The building itself was stunning, and the entirety of Lincoln Center was absolutely incredible: so much talent and art shoved into one concentrated area in New York. Although our seats weren’t the best, I actually thought they were perfect. From our row, I was able to not only watch the opera, but watch the orchestra, see the architecture of the room (those chandeliers were insane!), and see the reactions of the other audience members. Ultimately, my seat provided that perfect view to see the Opera House as a whole, rather than just the performance.

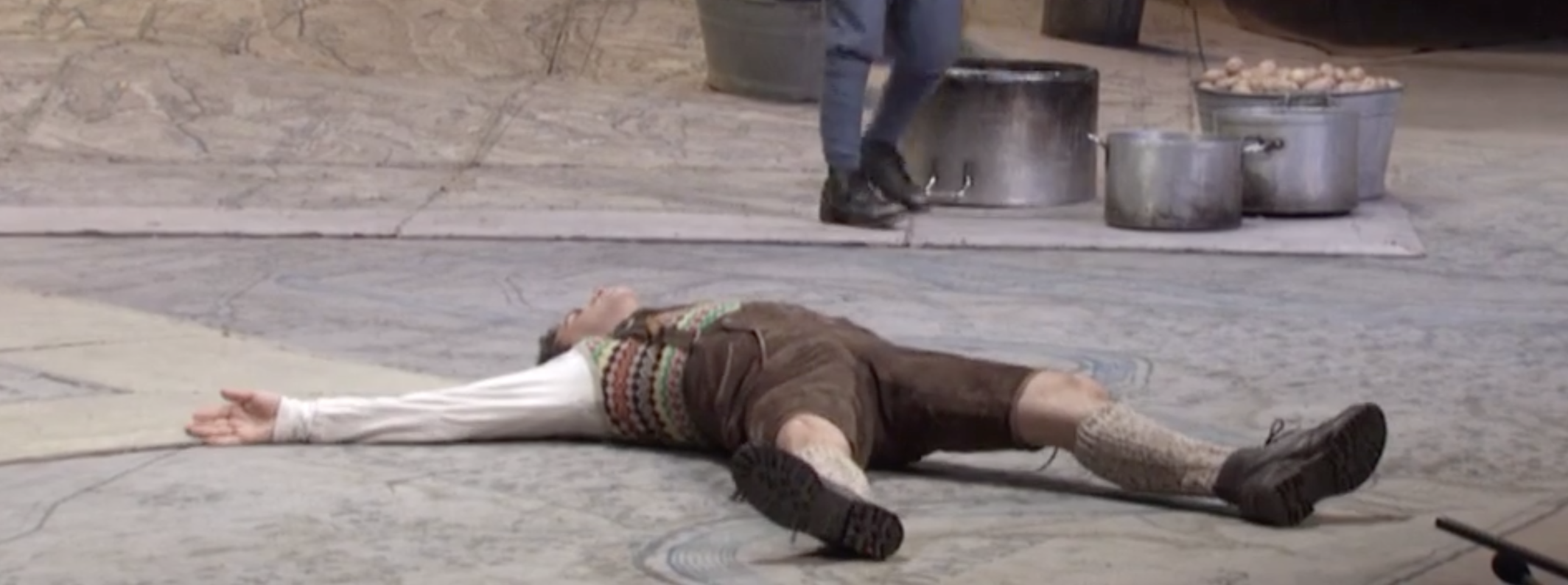

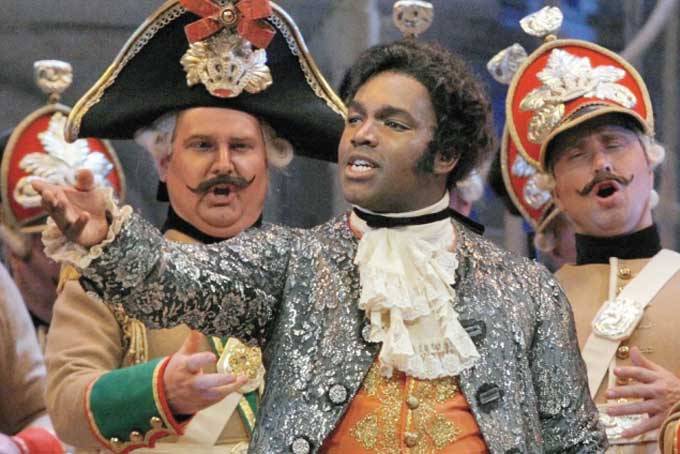

The show itself was incredible. Although I wished I hadn’t watched La Fille du Regiment online beforehand, it was astounding nonetheless. The performers were nothing less than incredible, but Marie definitely impressed me the most. The way she was able to hit outrageous notes with such ease, all the while staying in character and doing different actions around the stage simply took my breath away. I was impressed when hearing video recordings Marie’s arias, but it was nothing compared to hearing those arias live. My mom has a name for rare celebrities that have genuine talent that isn’t merely hyped up by society: she calls them the “real deal”. The woman playing Marie was without a doubt the real deal.

Aside from the performers, I enjoyed seeing the opera live. Most of the show was very similar to the tape we watched on Sakai, but the aspect of being live was much more enjoyable to watch. It’s obvious that there are different stylistic vocal and acting choices that every actor does different. I liked being able to know that those actors were putting everything they had into that performance, and that (almost) every audience was engaged in only the show. Additionally, I liked that the actors did not have microphones. I was worried I would spend a lot of the opera straining to hear the performers from our seats in the back, but every one of their voices carried throughout the entire room. I think the lack of microphones made the performance more authentic.

Although I did enjoy the performance tremendously, there were a few aspects that I did not enjoy that much. For starters, although I love listening to the vocalists sing, I don’t like that the show is very redundant in regards to the lyrics and the music itself. There were many parts such as Marie’s aria that were incredibly repetitive and I found myself zoning out. Also, I understand that it’s necessary that the characters exaggerate their lines and blocking; when I was watching the opera online, I was bothered by those exaggerations but it was easier to understand the necessity of them when watching it live in a room that large. However, I thought some of their reactions were a bit too dramatic and forced that it took away some of the authenticity for me and thus distracted me from the plot. However, these aspects did bother me enough to dislike the opera, as I left the opera house feeling very impressed nonetheless.

Aside from La Fille du Regiment itself, I had a great time people watching at the opera house and Lincoln Center in general. It’s obvious that there were a lot of audience members there that — like us — were simply there for the occasion of seeing the opera. However, there were also a few people I observed that were definitely part of NYC’s 1% — they were decked out in their pearls and fancy hats. I wouldn’t be surprised if those higher class individuals had season tickets and saw the opera as part of their weekly routine. It was entertaining to see the vastly different social classes present for that performance of the opera; all of us joining together for one afternoon of watching pure talent.

Ultimately, I came into this class being very ignorant of the operatic craft. However, in reflection, I realize that I am leaving the class being a much more experienced opera consumer, and I have gained several great friends (and professors!) that I am able to have intellectual conversations with to further cultivate our curiosity. Although I wouldn’t necessarily call myself a lover of opera (yet!), I have definitely gained more of an appreciation of the art form.